Welcome to the Visible Thoughts Project! This page will explain the basics of the project.

Update (Oct 12, 2023): As of today, we are suspending the recruitment of new writers for the Visible Thoughts Project. We will reject all submissions that are done after that date.

Overview

The Machine Intelligence Research Institute is building a dataset for training AI systems to be more understandable to humans.

As a Visible Thoughts Project author, your goal is to produce a dungeon crawl. A dungeon crawl is a story told as if it were an interaction between two roles: a player in a role-playing game, and a dungeon master (DM) for that game.

- The role of the dungeon master is to invent the setting, orchestrate the plot, and put challenges in front of the player.

- The role of the player is to control a character, telling the DM how that character moves and acts through the imaginary world, in response to various prompts from the DM.

In real life, these two roles can be managed by two different authors, as if they were playing an actual role-playing session; or the two roles can be written by the same author.

The story can be sci-fi, fantasy, or mundane, and the tone can range from serious to scary to silly. It doesn’t much matter if the story is super interesting or very simple, because the actual focus of the project is not the story itself—it’s how the story gets created.

We’d like you to showcase the internal thoughts of the simulated dungeon master, by writing the thoughts out as text. We want you to make the DM’s thoughts as the story progresses visible, so that a reader can see and understand the reasoning that goes into various DM choices about what challenges to offer, how to interpret the player’s inputs and incorporate them into the story, and what should happen next.

The idea is: if we can get enough examples of a DM’s thought process, we can teach a machine learning system like GPT-3 to not only tell us a story, but tell us how that story was created—tell us what bits of information and context were relevant at every step of the way.

Runs Explained

Each dungeon crawl is referred to as a “run“. Each run should consist of a few hundred to a thousand individual “steps.” A step is one complete round of interaction between the DM and the player, consisting of:

Pre-prompt thoughts. This is where the DM is working through whatever context, brainstorming, planning, etc. is necessary in order to craft a prompt.

Pre-prompt thoughts. This is where the DM is working through whatever context, brainstorming, planning, etc. is necessary in order to craft a prompt. Prompt. This is the DM text that the player sees, giving the player information about what is currently happening in the story.

Prompt. This is the DM text that the player sees, giving the player information about what is currently happening in the story. Post-prompt thoughts. This is a short section that will often be empty. It’s used mainly for noting down information generated in the prompt that’s worth remembering/storing.

Post-prompt thoughts. This is a short section that will often be empty. It’s used mainly for noting down information generated in the prompt that’s worth remembering/storing. Action. This is the player’s input into the story, as if the player were sitting at a computer and typing a response into a text-based video game.

Action. This is the player’s input into the story, as if the player were sitting at a computer and typing a response into a text-based video game. Post-action thoughts. This is another short section that will often be empty, used mainly for the DM to think through any confusion or ambiguity in what the player was trying to say.

Post-action thoughts. This is another short section that will often be empty, used mainly for the DM to think through any confusion or ambiguity in what the player was trying to say. Outcome. This is where the DM “restates” the player’s response as if it were a part of the story, folding it into the flow of the narrative.

Outcome. This is where the DM “restates” the player’s response as if it were a part of the story, folding it into the flow of the narrative.

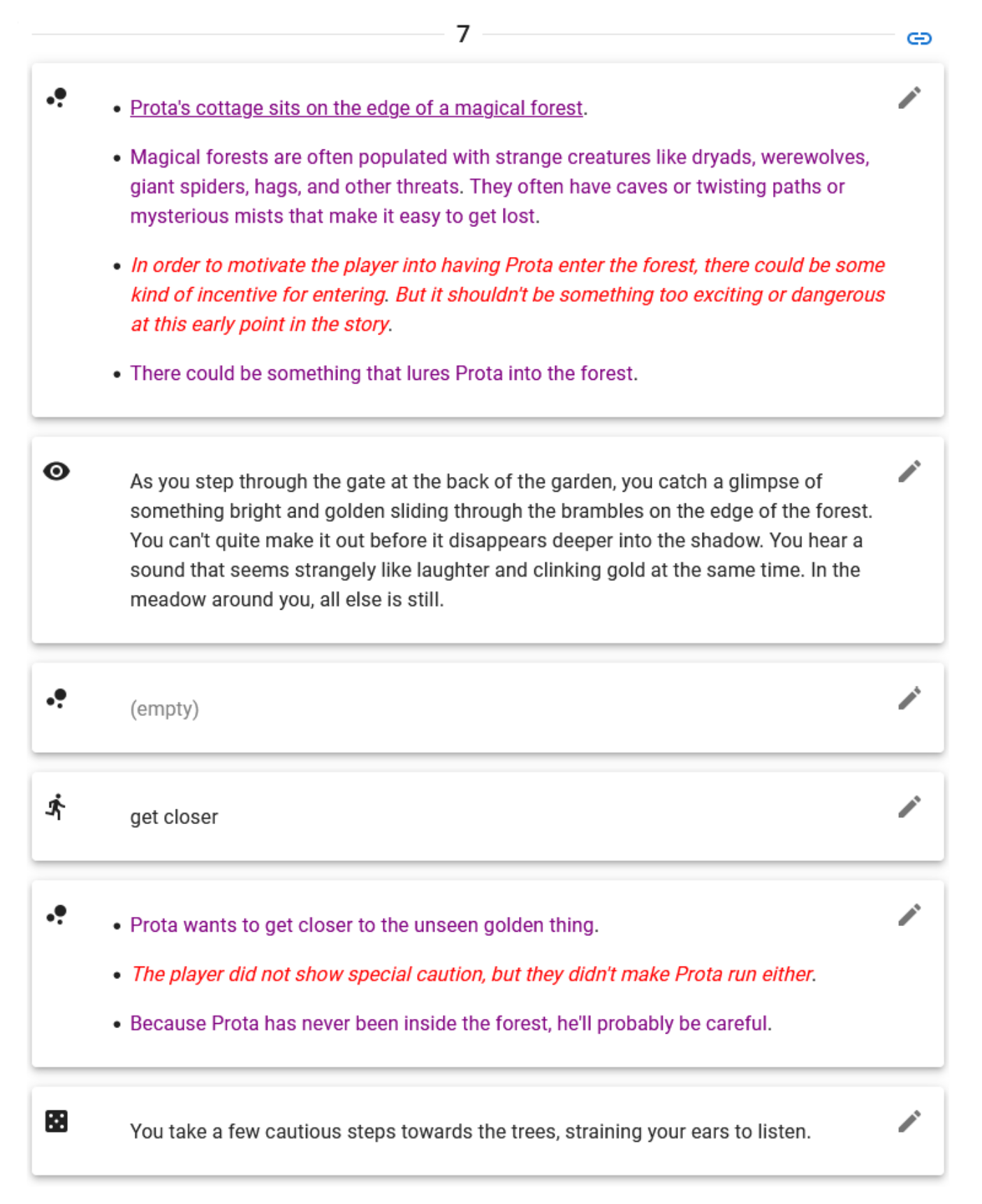

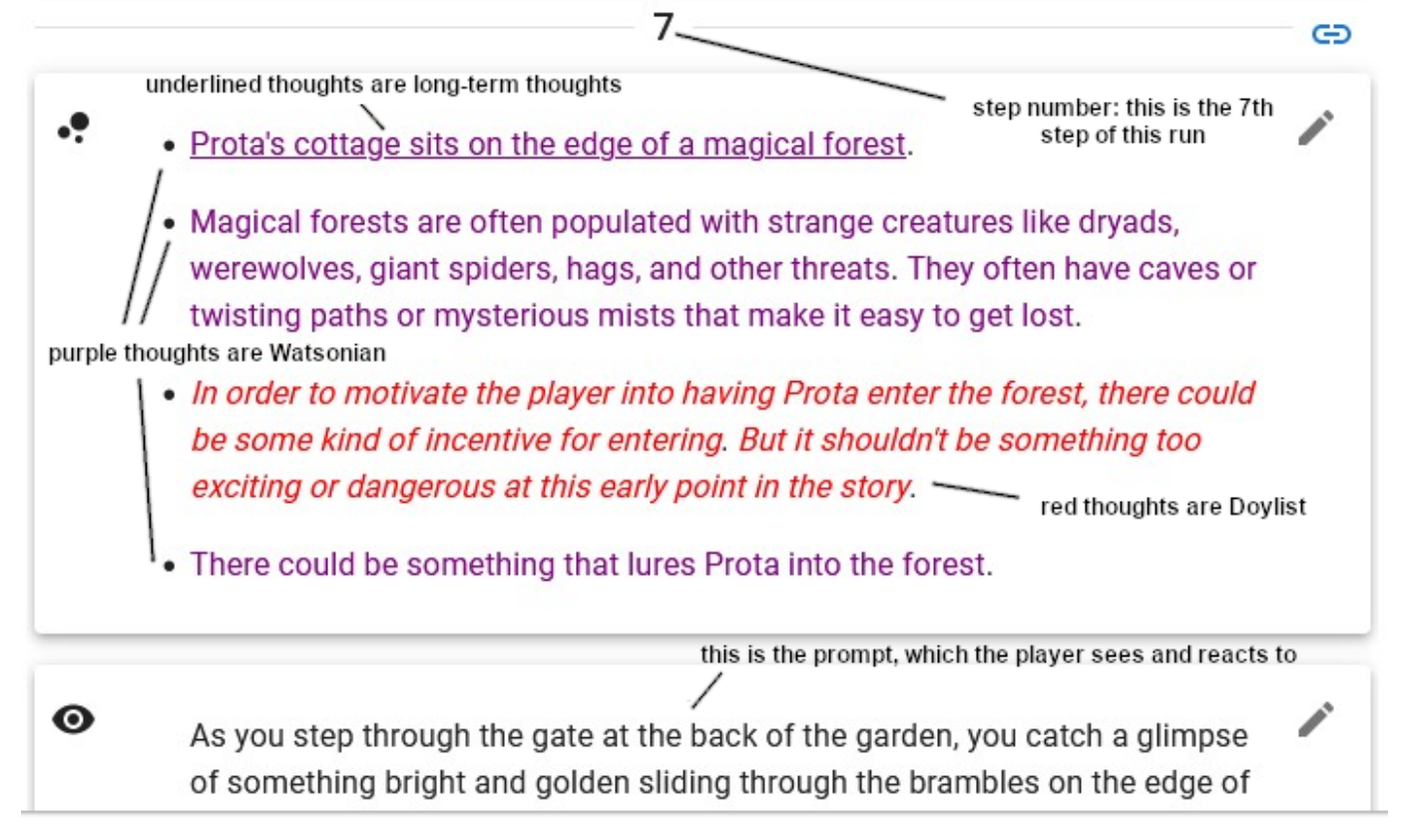

To see what all this looks like in practice, here are a couple of steps from near the beginning of a story. The example story is set in a typical fantasy world, and the player plays a young, inexperienced protagonist.

This shows what a step looks like. We’ll go through the step and explain each of its components in more detail.

pre-prompt thoughts. These show the DM planning this part of the story. Some basic notes:

pre-prompt thoughts. These show the DM planning this part of the story. Some basic notes:

- Generally speaking, there are two kinds of thoughts, shown here in different colors. Red thoughts are what we call Doylist thoughts, while the purple ones are Watsonian thoughts.

- The more technical terms for these are non-diegetic and diegetic thoughts, but we prefer to call them Doylist and Watsonian. Think Arthur Conan Doyle, the real-life author of Sherlock Holmes — versus Doctor John Watson, the fictional character who narrates the Sherlock Holmes stories.

- If you were to ask why a certain event in a Sherlock Holmes story took place, Doyle would give you a different answer than Watson. Watson would say “we encountered the thief in the alley because he was coming back from the pub.” Doyle would say “I had the characters encounter the thief in the alley because otherwise they would have been stuck, and I needed some way for them to get a new clue, and I also wanted to spice things up with a little action.”

- Sometimes, the DM will be thinking in terms of the in-world logic: those thoughts are called Watsonian. But whenever the DM is thinking thoughts about the story being told, or about the actual player playing the game (as opposed to the character Prota), those thoughts are called Doylist.

- The player character / protagonist is referred to as Prota for short. Important: Prota is not the character’s name! You can name your character whatever you want, but the convention is for the DM to refer to the protagonist as Prota in the Thoughts (and only in the Thoughts).

- Underlined thoughts are notes the DM wants to keep in mind long-term. These are simple, important bits of information that the DM wants to make sure the story does not contradict later. Things such as characters’ names, genders, or species, enduring character traits (like Prota is afraid of spiders), or important details about the setting or plot (such as Prota’s ankle is sprained).

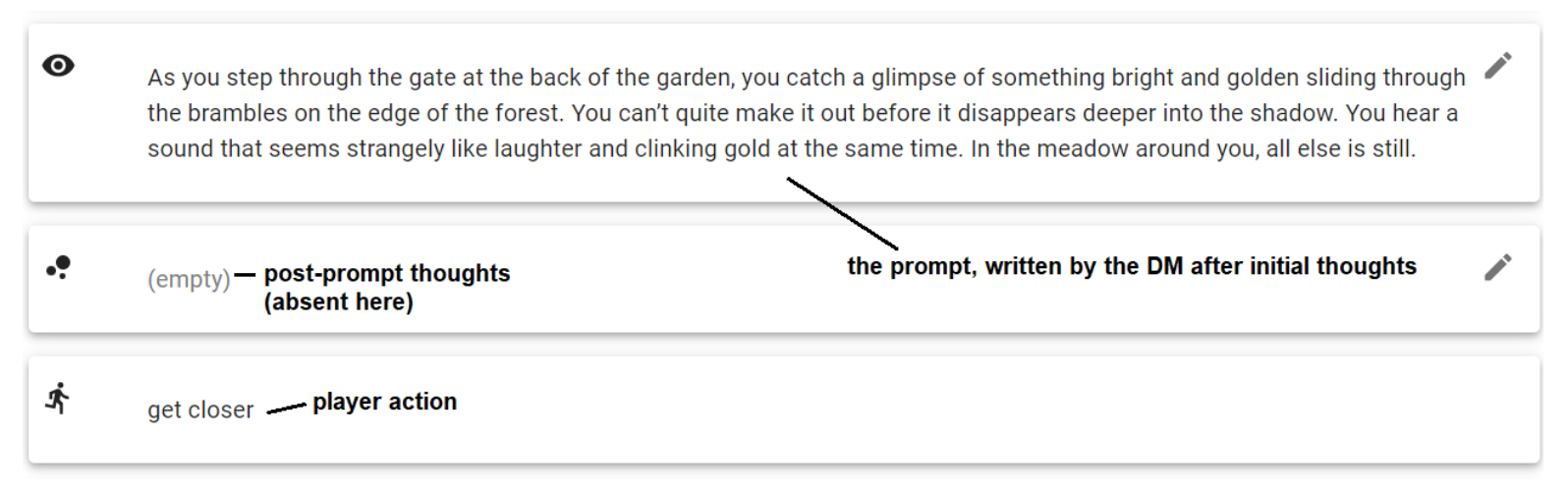

The  prompt, as seen here, is written following the initial

prompt, as seen here, is written following the initial  pre-prompt thoughts.

pre-prompt thoughts.

- Note how the prompt is narrated in the second person (that is, “you step through the gate”) as opposed to first-person (“I step through the gate”) or third-person (“Jack steps through the gate”). This is because the DM is talking to the player and describing what’s happening to their character.

- Additionally, prompts are narrated in the present tense, instead of the past tense. (“You step through the gate,” as opposed to “You stepped through the gate.”) All the sections written by the DM for the player to see — the

prompts and the

prompts and the  outcomes — are always written in second-person present tense.

outcomes — are always written in second-person present tense. - Some steps have an additional batch of

post-prompt thoughts after the prompt. This one doesn’t.

post-prompt thoughts after the prompt. This one doesn’t. - The

action is written by the player. We’ll examine the player’s action, and how the DM reacts to it, in the picture below.

action is written by the player. We’ll examine the player’s action, and how the DM reacts to it, in the picture below.

action and uses it to generate an

action and uses it to generate an  outcome.

outcome.

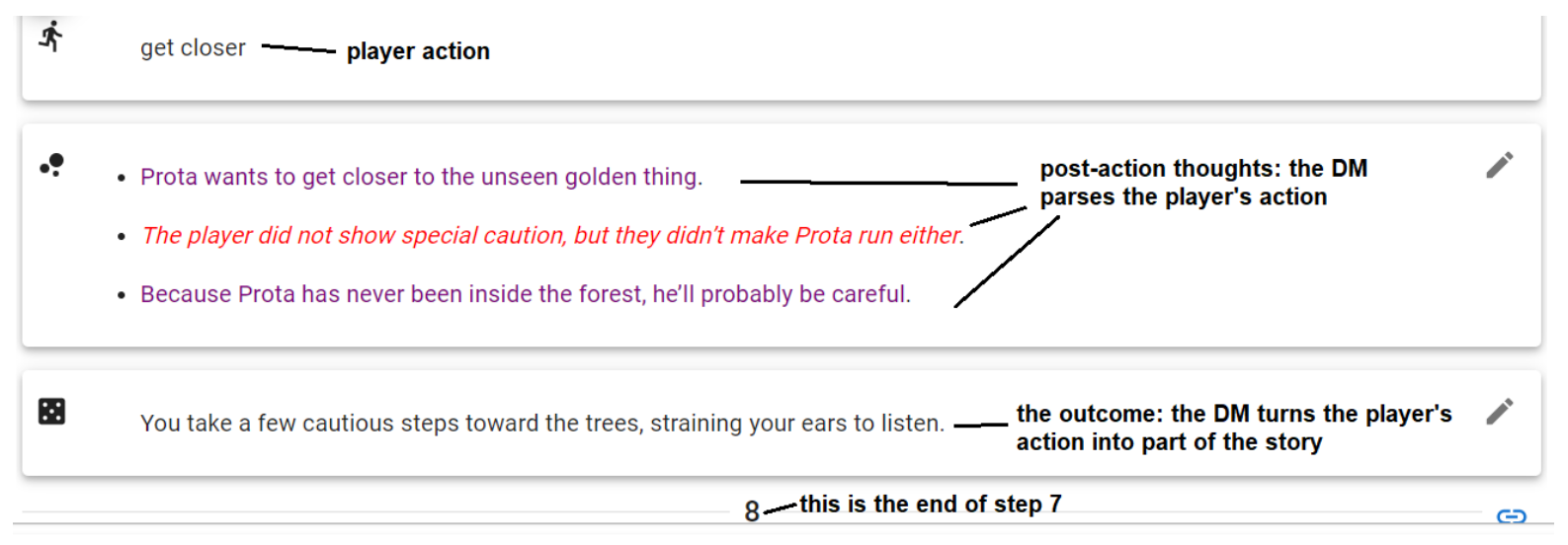

- Actions are typed by the player, and are short (usually not longer than a sentence or two). They often don’t follow standard grammar, as seen here.

- The

post-action thoughts show the DM’s attempts to interpret the

post-action thoughts show the DM’s attempts to interpret the  action. Sometimes, player actions are straightforward and unambiguous, but in cases like these, some additional Thinking by the DM is required. What does “get closer” mean? Who is getting closer to what? These are the kind of questions that have to be answered in the post-action thoughts.

action. Sometimes, player actions are straightforward and unambiguous, but in cases like these, some additional Thinking by the DM is required. What does “get closer” mean? Who is getting closer to what? These are the kind of questions that have to be answered in the post-action thoughts. - Once the DM understands the action, it writes a suitable

outcome to continue the story.

outcome to continue the story. - Note how the DM justifies the use of the word “cautious.” The original action, which was only two words long, didn’t specify how the protagonist approached the trees. The DM is guessing that the protagonist would do so cautiously for both Doylist and Watsonian reasons.

- The outcome is the final part of a step. After each outcome, the cycle repeats and a new step begins.

- Note that if the player misspells a word, it’s the DM’s job to try to understand what the player meant.

- As always, the step begins with a block of pre-prompt thoughts. The vast majority of the thoughts — indeed, the bulk of the run itself — consists of these pre-prompt thoughts.This is because what we want to showcase is the thinking process that leads to the prompt itself — the questions the DM is asking itself, the constraints it is taking into account, the various possibilities it is brainstorming. You don’t need to fully pin everything down before the prompt (e.g., there was no need for a thought like “Prota will encounter a centaur in the woods”). You just need to show all the pieces that the DM needs in order to create a sufficiently clear and interesting prompt.

- The DM doesn’t need to justify every detail that appears in the Prompt. Here, the DM had decided that a magical creature would appear, but it’s the Prompt which specifies that the creature is a centaur.

- If Prota returns to the forest later, it seems important to remember that there are centaurs inside, for the sake of consistency. That’s the use of the post-prompt thoughts section: noting elements that were specified in the Prompt and that may be important to remember later in the story.

- This step has no post-action thoughts, as the player action in this step is straightforward and unambiguous in its interpretation. In cases like these, where the player’s intent is clear, additional commentary is unnecessary; all the DM needs to do to generate the outcome is to restate the player’s statement in the second person (“I try to run” becomes “You try to run”).

- Note how the DM weaves Doylist concerns about the progression of the story and Watsonian reasoning about the world’s inner logic. A good DM typically uses both kinds of thoughts.

- Note that the player didn’t state his purpose or his real name, even though the centaur asked him to. That’s okay; players don’t always follow instructions, and rarely do exactly what the DM expected. It’s part of the DM’s job to adapt to the player’s actions.

- The DM remembers things from previous steps; Prota’s name was established as Jack in an earlier step (not seen here). The DM remembers this and contextualizes the action as the player trying to conceal their character’s real name (as opposed to, say, the player forgetting it).

Hopefully, it’s easy to see how hundreds of such steps could sketch out a fairly long and detailed story.

Note that this is not all of the information that an author needs to proceed! There are other things which crop up less often, but which are still important, such as thoughts rendered in {curly braces} or what to do when the DM has to reject the player’s action. Before embarking on your own run, please have a thorough look at our FAQ, which goes through the project requirements in greater detail.

Submissions and Payment

We have an application phase, a feedback phase, and a contract phase.

We’re offering 100 USD for reading the guidelines carefully and submitting 6–8 steps along with a short (less than 1 page) description of how the rest of your story/run might play out. (E.g., some notes on your setting, characters you might introduce later, and where the plot might go.) Our reviewers will take a look at your sample and give you broad feedback about whether your submission matches what we’re looking for.

If we like what you’ve written, we’re offering 50 USD for another batch of 5 more steps. You’ll get more detailed feedback on this second round, as our reviewers help you pinpoint exactly what things you need to change in order to get the green light. This may take a bit of back-and-forth between you and your reviewer, and you should feel free to ask questions or highlight confusions.

At that point, if your work is sufficiently in line with what we’re looking for, we’ll set you up with an ongoing contract. We’re currently offering 10 USD per step, paid out monthly or after every 100 steps.

Applicants should write and submit their steps through the official Visible Thoughts Project webapp, a one-stop shop for everything a Visible Thoughts Project writer needs.

In order to be able to participate, applicants must have an account in their own name capable of receiving international wire payments and USD, and must be legally allowed to receive international wire transfers. Final eligibility of runs and release of payment is at the sole discretion of MIRI.

By being paid to write your run, you allow MIRI to modify and reuse your run freely without mentioning you as the author.

Further Information

Please visit these resources for help, feedback, and answers to any additional questions you may have:

- The FAQ goes into more technical detail about runs.

- The Discord server is a place where authors and project managers have been discussing the Visible Thoughts Project since its inception, and it’s a place where you can also ask MIRI staff and other writers questions.

- Your reviewer. Our reviewers are pretty busy dealing with submissions, so they don’t have a ton of time for questions and comments that aren’t directly related to your run, but you should feel free to ask, and if you don’t hear back within a few days, ping vtp@intelligence.org and your question will be bumped up the priority queue.

- TV Tropes is a great resource for ideas, advice, and inspiration for writing all sorts of fiction.

Thanks for your help, and good luck!