Nick Beckstead recently finished a Ph.D in philosophy at Rutgers University, where he focused on practical and theoretical ethical issues involving future generations. He is particularly interested in the practical implications of taking full account of how actions taken today affect people who may live in the very distant future. His research focuses on how big picture questions in normative philosophy (especially population ethics and decision theory) and various big picture empirical questions (especially about existential risk, moral and economic progress, and the future of technology) feed into this issue.

Nick Beckstead recently finished a Ph.D in philosophy at Rutgers University, where he focused on practical and theoretical ethical issues involving future generations. He is particularly interested in the practical implications of taking full account of how actions taken today affect people who may live in the very distant future. His research focuses on how big picture questions in normative philosophy (especially population ethics and decision theory) and various big picture empirical questions (especially about existential risk, moral and economic progress, and the future of technology) feed into this issue.

Apart from his academic work, Nick has been closely involved with the effective altruism movement. He has been the director of research for Giving What We Can, he has worked as a summer research analyst at GiveWell, and he is currently on the board of trustees for the Centre for Effective Altruism, and he recently became a research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute.

Luke Muehlhauser: Your Rutgers philosophy dissertation, “On the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future,” argues that “from a global perspective, what matters most (in expectation) is that we do what is best (in expectation) for the general trajectory along which our descendants develop over the coming millions, billions, and trillions of years.”

In an earlier post, I summed up your “rough future-shaping argument”:

Astronomical facts suggest that humanity (including “post-humanity”) could survive for billions or trillions of years (Adams 2008), and could thus produce enormous amounts of good. But the value produced by our future depends on our development trajectory. If humanity destroys itself with powerful technologies in the 21st century, then nearly all that future value is lost. And if we survive but develop along a trajectory dominated by conflict and poor decisions, then the future could be much less good than if our trajectory is dominated by altruism and wisdom. Moreover, some of our actions today can have “ripple effects” which determine the trajectory of human development, because many outcomes are path-dependent. Hence, actions which directly or indirectly precipitate particular trajectory changes (e.g. mitigating existential risks) can have vastly more value (in expectation) than actions with merely proximate benefits (e.g. saving the lives of 20 wild animals).

One of the normative assumptions built into the rough future-shaping argument is an assumption you call Additionality. Could you explain what Additionality is, and why some people reject it?

Nick Beckstead: I think it may be helpful to give a bit of background first. I like to tackle the question of “how important is the far future?” by dividing the future up into big chunks of time (which I call “periods”), assigning values to the big chunks of time, and then assigning a value to the future as a function of the value assigned to the big chunks of time. You could think of it as creating some kind of computer program which would scan whole history of the world together with its future, carve it up into periods, scan each period and assign it a value, and then compute a value of the whole as a function of the value of its parts. It’s arbitrary how you carve up periods, but that’s okay because it’s an approximation technique. I think the approximation technique gives useful and reasonable answers if you make the periods quite large (spanning hundreds, thousands, or more years at once; you might want to carve it up into large batches of intelligent activity if you are considering future civilizations very different from our own).

Additionality basically says that when you’re assigning value to future periods, when you’ve got periods that you’d assign as “good,” it’s always better to have a period that you’d assign as good than periods you’d assign as “neutral.” I’m trying to partly draw on our intuitive ways of determining how well things have been going in recent history, and extending that to future periods, which we may be less capable of valuing using other methods. I want to say that if you had some future period which you’d regard as “good” judged purely on the basis of what happens in that period itself, that should contribute to the value you assign to the whole future.

You might disagree with this if you have what some philosophers call a strict “Person-Affecting View“. According to strict Person-Affecting Views, the fact that a person’s life would go well if he lived could not, in itself, imply that it would be in some way good to create him. Why not? Since the person was never created, there is no person who could have benefited from being created. On this type of view, it would only be important to ensure that there are future generations if it would somehow benefit people alive today, or people who have lived in the past (perhaps by adding meaning to their lives). The idea is that ensuring that there are future generations is analogous to “creating” many people, and, on this view, “creating” people–even people who would have good lives–can’t be important except insofar as it is important for people other than those you’re creating.

You might also disagree with this view if you think that “shape” considerations are relevant. One example of this is an average type view. You might say that adding on extra periods that are good, but of below average quality, is a bad thing. Or you might say that adding on extra periods that are not as good as the preceding ones can be bad because it could mean that things are getting worse over time.

I feel there are a lot of qualifications and details that need to be fleshed out here, but hopefully that should give some kind of reasonable introduction to the idea.

Luke: When I talk to someone about how much I value the far future, it’s pretty common for them to reply with a Person-Affecting View, though they usually don’t know it by that name. My standard reply is, “I used to have that view myself, but then I encountered some ideas that changed my mind, and made me think that, actually, I probably do care about future people roughly as much as I care about current people.” Then I tell them about those ideas that changed my mind.

I usually start with the block universe idea, which seems to be the default view among physicists (see e.g. Brian Greene & Sean Carroll, though I also like the explanation by AI researcher Gary Drescher). According to the block universe view, there is no privileged “present” time, and hence future people exist in just the same way that present people do.

But in the two chapters you spend arguing against “strict” and “moderate” Person-Affecting Views, you don’t refer to the block universe at all. Do you think the block universe fails to provide a good argument against Person-Affecting Views, or was it simply one line of argument you didn’t take the time to elaborate in your thesis?

Nick: I agree with your view about the block universe. I don’t think it is a strong argument against Person-Affecting Views in general, though I think it is a good argument against certain types of Person-Affecting Views. I think Person-Affecting Views are messy in many ways, and there are other lines of argument that I could have pursued but did not.

Another way to put the basic idea behind Person-Affecting Views is to say that, on these views, you divide people who may exist depending on what you choose into two classes: the “extra” people and the other people. And then you say that if you cause some “extra” people to exist with good lives, either that isn’t good or is less good than helping people who aren’t “extra.” Following Gustaf Arrhenius, in chapter 4 of my dissertation, I consider four different interpretations of extra: the people that don’t presently exist (Presentism), the people that will never actually exist (Actualism), the people whose existence is dependent on which alternative (of perhaps many) we choose (Necessitarianism), and the people that exist in one alternative being compared, but not the other (Comparativism).

As far as I can tell, only Presentism is undermined by the block universe critique, since only Presentism relies on a concept of “present.” This is why I said that the block universe critique only undermines certain versions of Person-Affecting Views.

The block universe argument seems like a knock-down argument against a very precise version of Presentism (which philosophers defending the view may hold), but I don’t think that it is a knock-down argument against a steel-manned, “rough and ready” version of the view. Someone might say, “Well, yes, I accept the block universe theory, so I acknowledge there is no physically precise thing for me to mean by “present.” But we can, in ordinary English, say sentences like “The world population is now approximately 7 billion.” And you understand me to be saying something intelligible and correct in some approximate sense. In a similar way, when I recommend that we only consider benefits which could come to people now living, I intend you to understand me similarly. I also hold that, right now, it is not practically useful to consider potential benefits to people who may exist in distant parts of the universe, so it doesn’t particularly matter which reference frame you use to approximately interpret my use of “present.” Though my view may not correspond to a clean fundamental distinction, I believe that this recommendation, for our present circumstances, would survive reflection more successfully than other views on this question which have been proposed.”

One can respond to this line of thought by arguing that even rough and ready versions of Presentism have consequences that are hard to accept, and aren’t motivated by appealing theoretical considerations. This is the approach I take in chapter 4 of my dissertation. I believe this line of argument is more robust against a wider variety of alterations of Person-Affecting Views.

Luke: Yeah, I guess I tend to use the block universe not as an argument but as an intuition pump for the view that “current” people aren’t so privileged (in a moral sense) as one might naively think.

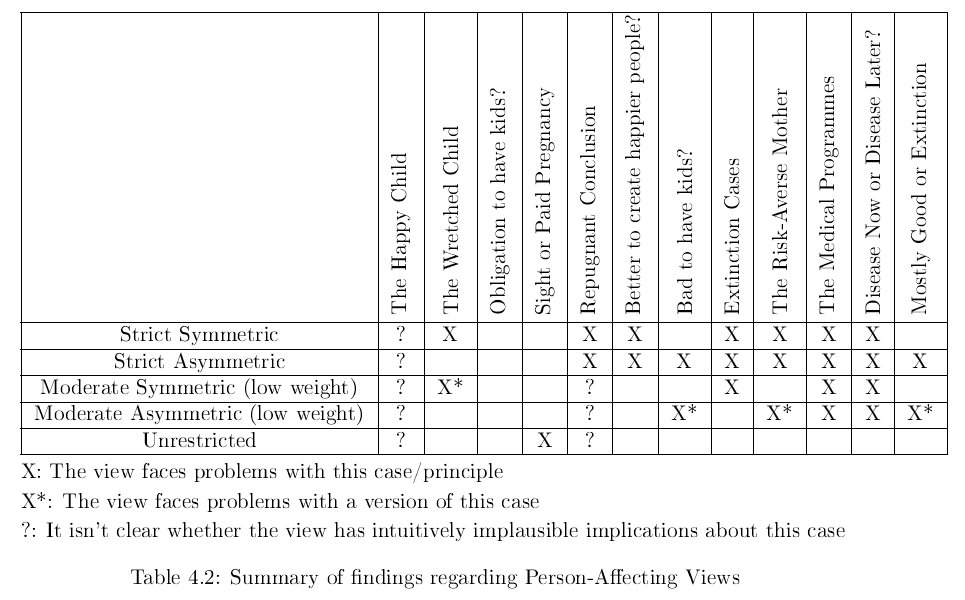

Anyway: in chapter 4 you survey a variety of thought experiments that have varying implications for Person-Affecting Views. At the end of the chapter, you provide this handy summary table:

Could you tell us what’s going on in this table, and maybe briefly hint at what a couple of the individual thought experiments are about?

Nick: In chapter 2 of my dissertation, I write about methodology for moral philosophy and argue that intuitive judgments about morality are in many ways less reliable than one might have hoped, and are often inconsistent. One of the consequences of this is that finding just a few counterexamples is often not enough to reject a moral theory. I believe it is important to systematically explore a wide variety of test cases and then proportion one’s credence to the theories that fare best over the whole set of cases.

The rows have different types of theories, and the columns are different types of test cases for the theories. And then I have marked the cases where the theories have implications that are hard to accept. Regarding the terminology in the columns, I call a Person-Affecting View “strict” if it gives no weight to “extra” people, and “moderate” if it gives less weight to “extra” people than other people. There is then a question about how much weight you give, and this table focuses on the cases where little weight is given to “extra” people.

I call a Person-Affecting View “asymmetric” if people who have lives that are not worth living are never counted as “extra.” People with Person-Affecting Views often want their views to be asymmetric because they want to be able to say that it would be bad to cause a child to exist whose life would be filled with suffering. (Derek Parfit has a famous case called “The Wretched Child” in Reasons and Persons, which is where I got this name. Reasons and Persons is probably my favorite book of moral philosophy.)

A major problem with strict Person-Affecting Views is that they have very implausible consequences in cases of extinction. It is one thing to say that the future of humanity isn’t overwhelmingly important, but quite another to say that it basically doesn’t matter if we go extinct, except insofar as it lowers present people’s quality of life.

Moderate Person-Affecting Views have implausible implications in certain fairly mundane cases where we are choosing between improving the lives of “extra” people or people who aren’t “extra”. A simple example is a case I call “Disease Now or Disease Later,” where we must choose between a public health program that would present some disease from hurting toddlers alive today, or a public health program that would help prevent a greater number of toddlers (who aren’t yet alive) in a few years from now. It is hard to believe that because the other toddlers don’t exist yet and which toddlers exist in the future might depend on which program we choose, it would be better to choose the first program. But that is what moderate Person-Affecting Views imply, since they give less weight to the interests of the toddlers who are counted as “extra”.

I call views which don’t make any distinction between regular people and “extra” people “Unrestricted Views.” Some philosophers believe that these views have imply that individuals are obligated to have children for the greater good, whereas Person-Affecting Views do not. However, there is no clear implication from “it would be good for there to be additional happy people” to “people are typically obligated to have children.” Why not? At least for people who don’t already want to have additional children, it would be very demanding to ask people to have additional children. Moreover, even on a view that gives a lot of weight to creating additional people, having additional children doesn’t seem like a particularly effective way of doing good in the world in comparison with things like donating money and time to charity. So it would be strange if people were obligated to make potentially significant sacrifices in order to do something that actually wasn’t all that effective as a method of doing good.

Basically, the rest of this table is a result of systematically checking these different views against a variety of test cases like these to see which have the most plausible implications overall. Of all these views, only a strict Person-Affecting View can plausibly be used to rebut the case for the overwhelming importance of shaping the far future. And this type of view is much less plausible than the alternatives.

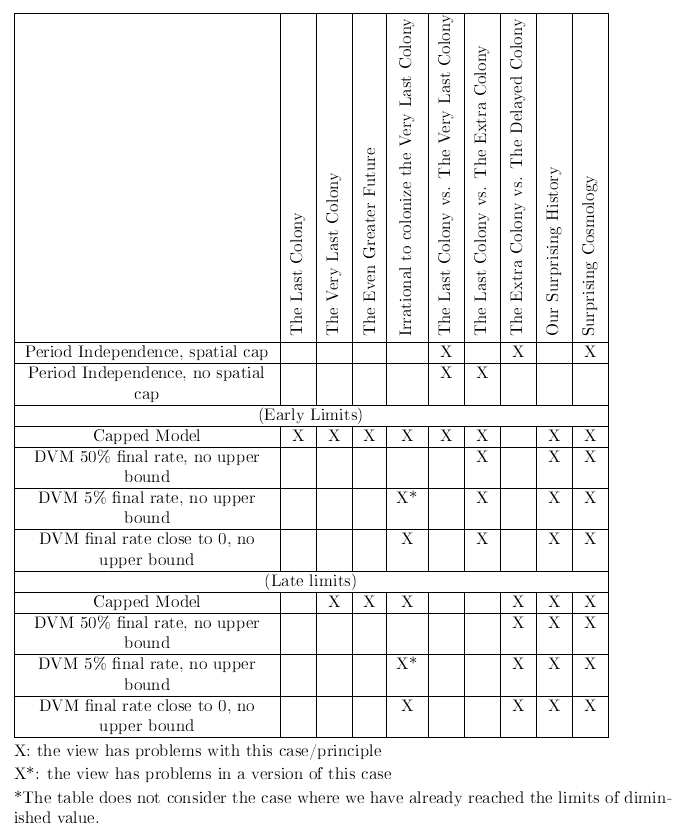

Luke: In chapter 5 of your dissertation you consider the question “Does future flourishing have diminishing marginal value?” Your summary table at the end of that chapter looks like this:

Could you explain what’s going on in this one, too?

Nick: In my dissertation, I defend using the following principle to evaluate the importance of the far future:

Period Independence: By and large, how well history goes as a whole is a function of how well things go during each period of history; when things go better during a period, that makes the history as a whole go better; when things go worse during a period, that makes history as a whole go worse; and the extent to which it makes history as a whole go better or worse is independent of what happens in other such periods.

Together with other principles I defend, this leads to the conclusion that you can generally approximate the value of the history of the world by assigning a value to each period, and “adding up” the value across periods.

Another way to get a grip on what Period Independence is a partial answer to is to consider the following hypothetical. Imagine that humans survive the next 1000 years, and their lives go well. How good would it be if they survived for another thousand years, with the same or higher quality of life? What if they survived another thousand years beyond that? Consider three kinds of answer:

- The Period Independence answer: It would be equally as important in each such case.

- The Capped Model answer: After a while, it gets less and less important. Moreover, there is an upper limit to how much value you can get in this way.

- The Diminishing Value Model (DVM) answer: After a while, it gets less and less important. However, there is no upper limit to how much value you can get in this way.

This table summarizes the result of running different test cases against different versions of Period Independence, the Capped Model, and the Diminishing Value Model.

Probably the most important test case supporting Period Independence is the one I call “Our Surprising History.” It goes like this:

Our Surprising History: World leaders hire experts to do a cost-benefit analysis and determine whether it is worth it to fund an Asteroid Deflection System. Thinking mostly of the interests of future generations, the leaders decide that it would be well worth it. After the analysis has been done, some scientists discover that life was planted on Earth by other people who now live in an inaccessible region of spacetime. In the past, there were a lot of them, and they had really great lives. Upon learning this, world leaders decide that since there has already been a lot of value in the universe, it is much less important that they build the Asteroid Deflection System than they previously thought.

It seems unreasonable to claim that how good it would be to build the Asteroid Deflection System depends on this information about our distant past. But this is what Capped Models and Diminishing Value Models imply about this case.

Many of the cases in this table involve considering some simple test cases involving colonizing other planets. For example consider:

The Last Colony: Human civilization has lasted for 1 billion years, but the increasing heat of the sun will soon destroy all life on Earth. Humans (or our non-human descendants) get the chance to colonize another planet, where civilization can continue. They know that if they succeed in colonizing this planet, then: (i) the new planet will sustain a population equal to the size of the population of the Earth, and this planet, like Earth, will sustain life for 1 billion years, (ii) these people’s lives will probably go about as well the lives of the Earth people, (iii) there will not be a chance for the people on the new planet to colonize another planet.

Intuitively, it would be extremely important to colonize the extra planet in the second case, much more important than colonizing in the first case. But on a Capped Model, if you set the “upper limits” low enough, it might not be very important at all.

Diminishing Value Models avoid this implication, and can say that it would be extremely important to colonize another planet. They might also claim that their view has more plausible implications than Period Independence when comparing The Last Colony with a case like this:

The Very Last Colony: Convinced of the importance of preserving future generations, we take great precautions to protect the far future. Our descendants succeed in colonizing a large portion of the galaxy. It becomes relatively clear that our descendants will last for a very long time, about 100 trillion years, until the last stars burn out. At that point, there will be nothing of value left in the accessible part of the Universe. It comes to our attention that there is a chance to colonize one final place, just as in The Last Colony, before civilization comes to an end. For this billion years, these will be the only people in the accessible part of the Universe. During this period, things will go exactly as well as they went in The Last Colony.

In which case is colonization more important, The Last Colony or The Very Last Colony? According to Period Independence, it is equally as important in each case. According to Diminishing Value Models, it is less important in The Very Last Colony. I find DVM stance on this intuitively attractive, though I believe it is a product of a bias I call the proportional reasoning fallacy.

In chapter 2 of my dissertation, I argue that we use misguided proportional reasoning in some cases where many lives are at stake. Fetherstonhaugh et al. (1997) found that participants significantly preferred saving a fixed number of lives in a refugee camp when the proportion of lives saved was greater. Describing the participants’ hypothetical choice, they write:

There were two Rwandan refugee programs, each proposing to provide enough clean water to save the lives of 4,500 refugees suffering from cholera in neighboring Zaire. The Rwandan programs differed only in the size of the refugee camps where the water would be distributed; one program proposed to offer water to a camp of 250,000 refugees and the other proposed to offer it to a camp of 11,000.

Participants significantly preferred the second program. In another study, Slovic (2007) found that people were willing to pay significantly more for a program of the second kind.

All the views I consider have some implausible implications in certain cases, but it seems easier to explain away the test cases that look bad for Period Independence, and there are somewhat fewer of them, so I conclude that Period Independence is the most plausible principle to use for evaluating far future prospects. Of all these views, only Capped Model or a DVM with a very sharp diminishing rate in the limit can plausibly be used to rebut the case for the overwhelming importance of shaping the far future. And these views, I believe, are less plausible than the alternatives.

Luke: What’s a point you wish you could have included in your dissertation, that was left out for space or other reasons?

Nick: I’ll list a few. There are a lot of things that I think could be better, but you have to put your work out there at some point. Just as real artists ship, real thinkers share their ideas.

First, a core empirical claim in my thesis is that humans could have an extremely large impact on the distant future. Really, it’s sufficient for my argument that they would do this by existing for an extremely long time, or that there could be a very large number of successors (such as whole brain emulations or other AIs). I didn’t defend this claim as thoroughly as I could have, and I didn’t go into great detail because I feared that philosophers would complain that it “isn’t philosophy,” I wanted to finish my dissertation, and I thought that going into it would require a lot of background information due to inferential distance.

The second thing I’d like to add is related to chapter 2 of my dissertation. An abstract of that chapter goes like this:

I argue that our moral judgments are less reliable than many would hope, and this has specific implications for methodology in normative ethics. Three sources of evidence indicate that our intuitive ethical judgments are less reliable than we might have hoped: a historical record of accepting morally absurd social practices; a scientific record showing that our intuitive judgments are systematically governed by a host of heuristics, biases, and irrelevant factors; and a philosophical record showing deep, probably unresolvable, inconsistencies in common moral convictions. I argue that this has the following implications for moral theorizing: we should trust intuitions less; we should be especially suspicious of intuitive judgments that fit a bias pattern, even when we are intuitively confident that these judgments are not a simple product of the bias; we should be especially suspicious of intuitions that are part of inconsistent sets of deeply held convictions; and we should evaluate views holistically, thinking of entire classes of judgments that they get right or wrong in broad contexts, rather than dismissing positions on the basis of a small number of intuitive counterexamples. In addition, I argue that many of the specific biases that I discuss would lead us to predict that people would, in general, undervalue most of the available ways of shaping the far future, including speeding up development, existential risk reduction, and creating other positive trajectory changes.

I’m concerned that in chapter 2, there is an unbalanced focus on ways in which intuitions fail, and not ways in which trying to correct intuition through theory development could fail. An uncharitable analogy would be that it is as if I wrote a paper about all the ways in which markets can fail and suggested we rely more on governments without talking about all the ways in which governments can fail. And just as someone could write an additional chapter (or series of books) on how governments fail, someone could probably also write an important chapter on how people trying to correct intuitions with moral theory fail. So while I feel that the considerations I identify do speak in favor of the recommendations I make, I think there are also important considerations that speak against those recommendations which I did not mention, and probably should have mentioned.

Some of the considerations on the other side, some of them weak, include:

- Given Jonathan Haidt’s theory of social intuitionism–which seems very plausible to me–a lot of our theoretical reasoning about moral issues is epiphenomenal lawyering, and that makes theoretical reasoning about morality seem less reliable.

- Lots of moral philosophers have endorsed stuff that seems wrong after due consideration, and their views rarely seem superior to common sense when there are conflicts, despite the fact that many of them think they are different from other philosophers in these respects. (A possibly important exception to this is the views of early utilitarians, who opposed slavery, opposed bad treatment of animals, opposed bad treatment of women, opposed bad treatment of gay people, and favored various kinds of liberty quite early. One only has to compare the applied ethics of Kant and Bentham to get a sense of what I am talking about.)

- I have a rough sense that only a very limited amount of moral progress is attributable to people trying to use explicit reasoning to correct for intuitive moral errors, in contrast with people who just learned a lot of ordinary facts about problematic cases and shared them widely.

- As I discuss somewhat toward the end of the dissertation, when you try to correct for intuitive errors, it’s sort of like trying to patch a piece of software that you don’t understand. And it seems quite possible that the patching will introduce unanticipated errors in places where you didn’t know to look.

- People seem to have reasonably functional ways of handling internal inconsistency, so that inconsistent intuitions are probably less damaging than they can appear at first.

- A lot of our moral intuition comes from cultural common sense. When we try to correct cultural common sense, we can see what we’re doing as analogous to aiming for a type of innovation. Most attempts at innovation seem to fail. This type of analogy supports being cautious about correcting intuition with theory, and trying to present the theory in a way that is appealing to cultural common sense.

I’m still working through these issues, and hope to include them someday in a paper that is an improved version of chapter 2.

A third issue is that there was less discussion of how our altruistically-motivated actions should change once we accept the view that shaping the far future is overwhelmingly important. This is an enormously complex and fascinating issue that requires drawing together ideas from both highly theoretical and highly practical fields. I was thinking about this issue at the time I was writing the dissertation, but not during the whole time. And it doesn’t show up in the dissertation as much as I wish it did. This is again, in part, because I think too much discussion of the issue would result in people complaining that my work “isn’t philosophy.” (I expect this is a common challenge for people in academia with interdisciplinary interests.) I am thinking about this issue more now, and I’m glad that others have started to write stuff on this topic which I think is relevant.

A final issue is that I wish I had done more to flag is that it is complicated how to weigh up one’s moral uncertainty about the importance of shaping the far future. It’s possible that even if one mostly believes that shaping the far future is overwhelmingly important, we should not devote too much of our effort to a single type of concern. I believe this may be an implication of Bostrom and Ord’s parliamentary model of moral uncertainty, and may be a feature of other plausible ways of thinking about moral uncertainty that we could design. And this may make the implications of my thesis smaller than they would otherwise be, though I’m very unclear about how all this plays out. This is something I have not yet thought about very carefully at all.

Luke: Last question. In Friendly AI Research as Effective Altruism I paraphrased a point you made in your dissertation:

It could turn out to be that working toward proximate benefits or development acceleration does more good than “direct” efforts for trajectory change, if working toward proximate benefits or development acceleration turns out to have major ripple effects which produce important trajectory change. For example, perhaps an “ordinary altruistic effort” like solving India’s iodine deficiency problem would cause there to be thousands of “extra” world-class elite thinkers two generations from now, which could increase humanity’s chances of intelligently navigating the crucial 21st century and spreading to the stars. (I don’t think this is likely; I suggest it merely for illustration.)

So even if we accept your argument for the overwhelming importance of the far future, it seems like we need to understand many empirical matters — such as ripple effects — to know whether particular direct or indirect efforts are the most efficient ways to positively affect our development trajectory. Do you have any thoughts for how we can make progress toward answering the empirical questions related to shaping the far future?

Nick: There is an enormous amount of work and it is hard to say what will be most valuable. But here are a few ideas that seem promising to me right now.

One type of work that I think is valuable for this purpose is the type of work that GiveWell Labs is doing: figuring out what the landscape of funding opportunities is across different causes, analyzing how tractable and important various problems are, and so forth. Here I am including studying both highly targeted causes (such as directly attacking different global catastrophic risks) and very broad causes (such as improving scientific research). I would like it if more of this work were done on the “room for more talent” side in addition the “room for more funding” and “room for more philanthropy” stuff that GiveWell does. I hope 80,000 Hours takes up more of this type of research in the future as well. The sort of work that MIRI and FHI do on examining specific future challenges that humanity could face and what could be done to overcome them seems like it can play an important role here as well.

Another type of work that seems promising to me is to study a wide variety of unprecedented challenges that civilization has faced in the past in order to learn more about how well civilization has coped with those challenges, what factors determined how well civilization coped with those challenges, what types of efforts helped civilization cope with those challenges better, and what kinds of efforts could plausibly have been helpful. Studying the types of challenges that Jonah Sinick is asking about here seems like a step in the right direction. The type of work that GiveWell is supporting on the history of philanthropy would be relevant as well. This type of work seems like it could be reasonably grounded and could help improve our impressions about what types of broad approaches are most promising and where on the broad/targeted spectrum we should be.

It seems to me that a number of factors are often relevant for determining how well humanity handles a risk/challenge. At a very general level, these might be some factors like: how good a position people are in to cooperate with each other, how intelligent individuals are, how good the “tools” (like personal computers, software, conceptual frameworks) people have are, how good access to information is, and how good people’s motives are. Sometimes, what really matters is how key actors fare in specific ways during a challenge (like the people running the Manhattan project and the heads of state), but it is often hard to know which people these will be and which specific versions are relevant. These factors also interact with each other in interesting ways, and are interestingly related to general levels of economic and technological progress. There’s some combination of very broad economic theory/history/economic history that is relevant for thinking about how these things are related to each other, and I feel that having that type of thing down could be helpful. Someone with the right kind of background in economics could try to explain these things, or someone who has the right sense of what is important with these factors could try to summarize what is currently known about these issues. An example of a book in this category, which I greatly enjoyed, is The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth by Benjamin Friedman. As mentioned previously, I consider some of the work done by GiveWell on “flow-through” effects and some of the work done by Paul Christiano on the value of prosperity and technological progress to be relevant to this. I believe more work along these lines could be illuminating.

I recently gave a talk on this subject at a CEA event. In this talk, I lay out some very rough, very preliminary, very big picture considerations on this issue.

CEA slides.

Luke: Thanks, Nick!